INACTIVITY

Giorgio Agamben / Art, Inactivity, Politics

The divine government of the world is in fact something fundamentally finite. After the Last Judgment, when the history of the world and its creatures is at an end, when the elect have obtained eternal bliss and the damned their eternal retribution, the angels will have nothing more to do.

A totally idle god is a god without power, who has given up governing the world; this is the god the theologians find it impossible to accept. To avoid the total disappearance of all power, they separate power from the exercise of power and maintain that power does not disappear but that it is simply no longer exercised, thus it assumes the motionless, resplendent form of glory (doxa in Greek).

-----------------------------------glory and inactivity-----------------------------------

The most important Jewish festival, the shabat, had its theological foundation in the fact that it was not the work of creation but the cessation of all work on the seventh day that was declared sacred. Inactivity thus defines the state proper to God (“Only to God does inactivity (anapausis) really belong” writes Philon, “the Sabbath, which means inactivity, belongs to God” and, at the same time, is the object of eschatological expectations (“they shall not enter into my inactivity” – eis ten anapausin emou, Ps. 95, 11)).

The unspeakable mystery which glory, with its blinding light, is supposed to hide is the mystery of divine idleness, of what God did before creating the world and after the providential government of the world had reached its conclusion.

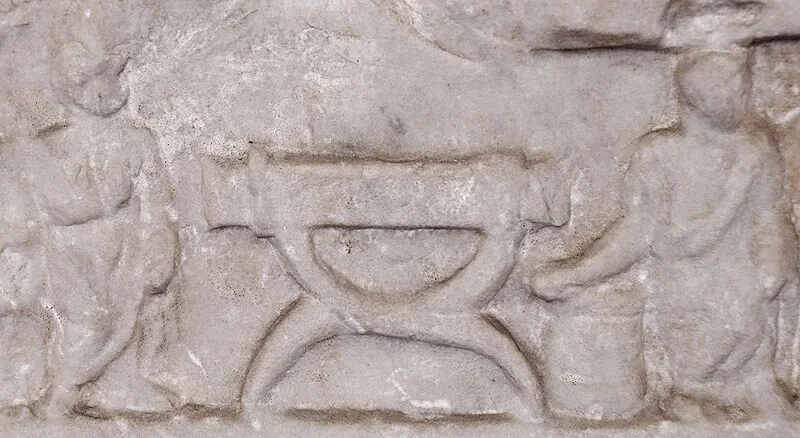

The majesty of the empty throne. Funerary relief with a sella curulis. Marble, Roman artwork, 50 BC–50 AD. From the Torre Gaia on the Via Casilina, Rome.

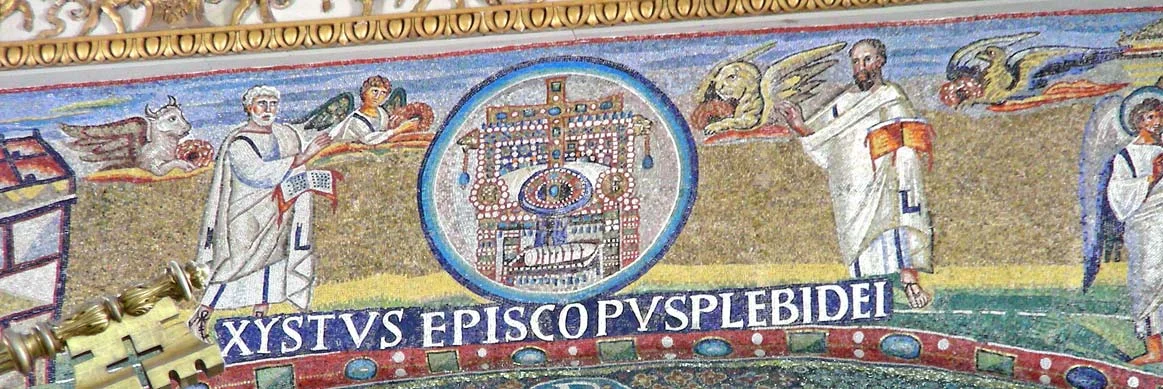

The mosaic in the arch of Sixtus iii in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome (fifth century) depicts an empty throne en‑ crusted with multicoloured stones on which rest a cushion and a cross; beside the throne can be glimpsed a lion, an eagle, a winged human figure, fragments of wings and a crown.

the empty throne

It is in Christian circles, however, in the majestic eschatological image of the hetoimasia tou thronou which adorns the triumphal arches and apses of Early Christian and Byzantine basilicas, that the religious significance of the empty throne reaches its climax.

Throne of Preparation, part of a Fresco of the Last Judgment (1300's, Serbia)

Historians generally interpret the image of the throne as a symbol of royalty, whether sacred or secular. Such an explanation cannot however account for the empty throne in the Christian hetoimasia. The term hetoimasia is, like the verb hetoimaso and the adjective hetoimos in the Greek translation of the Bible, a technical term which in the Psalms refers to the throne of Yahweh: “The Lord has prepared his throne in heaven” (Ps. 102, 19); “Ready (hetoimos) for ever is his throne” (Ps. 92. 2). Hetoimasia does not allude to the act of preparing or arranging anything; it alludes to the preparedness of the throne. The throne has always been ready and has always awaited the glory of the Lord. According to rabbinical Judaism, the throne of glory is one of the seven items Yahweh created before he created the world. Similarly, in Christian theology, the throne is eternally prepared because the glory of God is coeternal with it. The empty throne is not, therefore, a symbol of royalty but of glory. Glory precedes the creation of the world and survives unto its end. And the throne is not only empty because glory, although coinciding with the divine essence, is not identi‑ fied with it; and also because it is, in its heart of hearts, idleness. The supreme image of sovereignty is empty.

Inactivity does not in fact mean simply inertia, non‑activity. It refers rather to an operation which involves inactivating, de‑ commissioning (des‑oeuvrer) all human and divine endeavour.

Art is political in itself, because it is an operation which contemplates and renders non‑operational man’s senses and usual actions, thus opening them to new possible uses. For this reason art comes so close to politics and philosophy as almost to merge with them. What poetry achieves by the power of speech and art by the senses, politics and philosophy have to achieve by the power of action. By rendering biological and economic operations inactive, they show of what the human body is capable, they open the body to new possible uses.

vis inertiae

interview with Agamben

Thinking about inoperativeness, for example?

The insistence on work and production is a malign one. The Left went down the wrong path when it adopted these categories, which are at the centre of capitalism. But we should specify that inoperativeness, as I conceive it, is neither inertia nor idling. We must free ourselves from work, in an active sense – I very much like this French word désoeuvrer. This is an activity that makes all the social tasks of the economy, law and religion inoperative, thus freeing them up for other possible usages. For precisely this is proper to mankind: writing a poem that escapes the communicative function of language; or speaking or giving a kiss, thus changing the function of the mouth, which first and foremost serves for eating. In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle asked himself whether mankind has a task. The work of the flute player is to play the flute, and the cobbler's job is to make shoes, but is there a work of man as such? He then advanced his hypothesis according to which man is perhaps born without any task; but he soon abandoned it. However, this hypothesis takes us to the heart of what it is to be human. The human is the animal that has no job: it has no given biological task, no clearly prescribed function. Only a powerful being has the capacity not to be powerful. Man can do everything but does not have to do anything.

Leaving secondary school, I had just one desire – to write. But what does that mean? To write – what? This was, I believe, a desire for possibility in my life. What I wanted was not to 'write', but to 'be able to' write. It is an unconscious philosophical gesture: the search for possibility in your life, which is a good definition of philosophy. Law is, apparently, the contrary: it is a question of necessity, not of possibility. But when I studied law, it was because I could not, of course, have been able to access the possible without passing the test of the necessary. In any case, my law studies came to be very useful for me. Power has dropped political concepts in favour of juridical ones. The juridical sphere never stops expanding: they make laws on everything, in domains where it would once have been inconceivable. This proliferation of law is dangers: in our democratic societies, there is nothing that is not regulated. Arab jurists taught me something that I liked very much. They represent law as a sort of tree, with at one extreme what is forbidden and, at the other, what is obligatory. For them, the jurist's role is situated between these two extremes: that is, addressing everything that one can do without juridical sanction. This zone of freedom never stops narrowing, whereas it ought to be expanded.

also:

from:

Peter Cockelbergh - Marginalalia: On Pierre Joris Justifying

The concept of “un/working” is crucial here, and needs further elaboration. The word itself is Joris’s translation of “désoeuvrer” / “désoeuvrement,” and goes back to his 1988 translation of Maurice Blanchot’s La communauté inavouable. ‘Désoeuvrer, -é, -ement’ has been translated variously as ‘inoperable,’ ‘worklessness’ and ‘uneventfulness;’ Joris, however, opted for ‘unworking’ so as to maintain the ‘semantic range’ (UC, xxii-xxiii) as much as possible. The literal meaning of ‘être désoeuvré(e)’ is to be idle, to be at a loose end, unemployed, unoccupied, yet Blanchot expands the term tremendously, turning it into an active philosophical and literary concept. Crucial to that concept is the notion of ‘oeuvre:’ a literary or artistic work, both in the sense of a single book or work, and of the collective works or oeuvre of an author. In the preface to his translation, Joris quotes a passage from Blanchot’s L’entretien infinithat gives a good sense of what is at stake in the former’s essay books as well:

To write is to produce absence of the work (worklessness) [désoeuvrement]. Or: writing is the absence of the work as it produces itself through the work and throughout the work. Writing as worklessness [désoeuvrement] (in the active sense of the work) is the insane game, the indeterminacy that lies between reason and unreason.

What happens to the book during this “game,” in which worklessness [désoeuvrement] is set loose during the operation of writing? The book: the passage of an infinite moment, a movement that goes from writing as an operation to writing as worklessness [désoeuvrement]; a passage that immediately impedes. Writing passes through the book, but the book is not that to which it is destined (its destiny). Writing passes through the book, completing itself there even as it disappears in the book; and yet, we do not write for the book. The book: a ruse by which writing goes towards the absence of the book. (Blanchot, translated by Lydia Davis, quoted in UC, xxiii-xxiv)

Much I have excerpted from various sources.

Please note that I do not own the copyright to most of the texts, images, or videos.