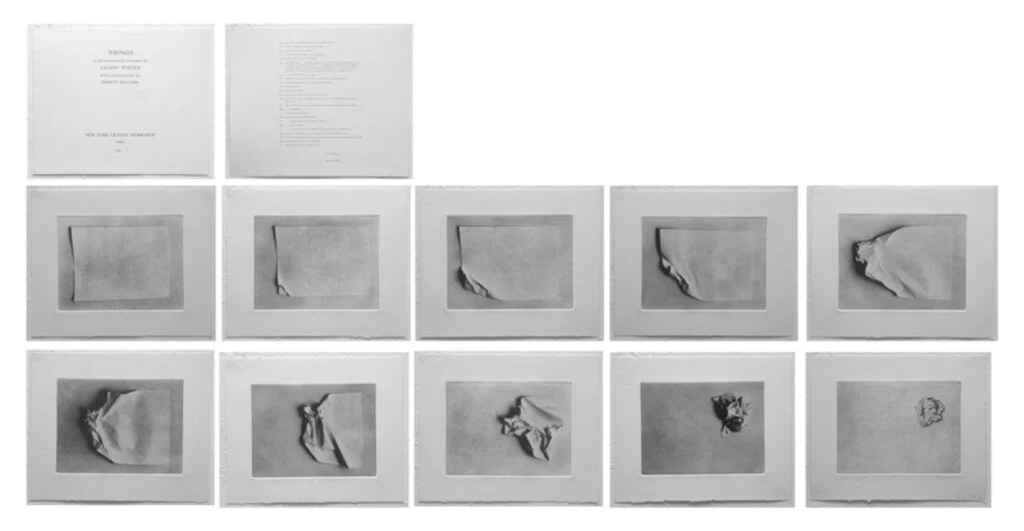

LILIANA PORTER

Wrinkle, 1968

Born in Buenos Aires, 1941

Studied at the Manuel Belgrano School of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires

Studied printmaking at the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City with Guillermo Silva Santamaria

Studied at the Escuela de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires

Moved to New York and co-founded the New York Graphic Workshop with Luis Camnitzer and Jose Guillermo Castillo in 1965

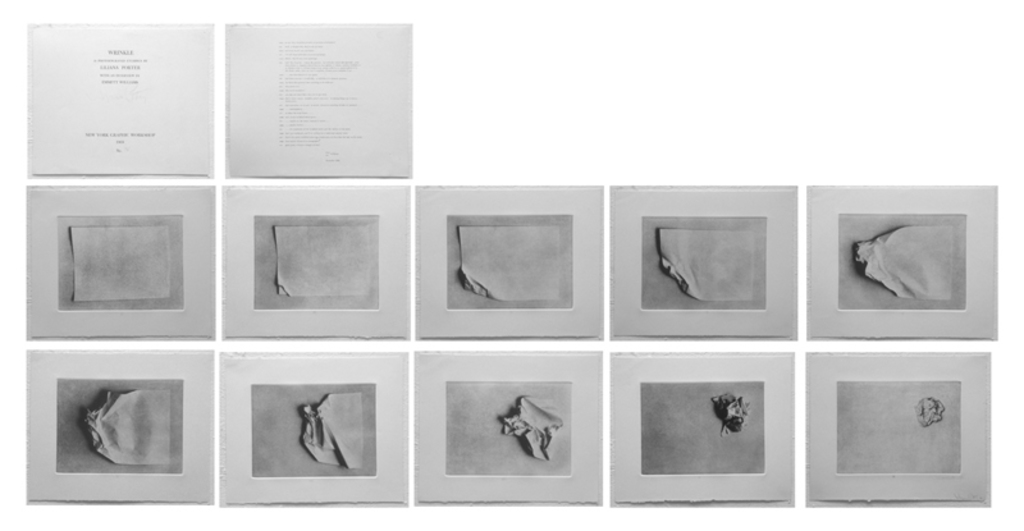

Untitled (Self-Portrait with Square), 1973

"A typical minimalist work of art would have been inconceivable, absurd, and I would even say ethically questionable, if created in a Latin American country. These artworks were very expensive to produce, and made possible by very advanced technologies...Pop works were also the direct result of a hyper-developed consumer society. All of those materials that were used for advertising in supermarkets ad on the streets simply did not exist in our countries, where we still carried a little cloth bag to go out and buy our bread."

"Now I realize that you can live here [New York (after 50 years)] a thousand years, but you will always be a foreigner. If you look at my CV, it's striking to see what a large percentage of my collectors and shows have to do with Latin America. There's no way around it: people are separated into categories here."

New York Graphic Workshop, 1964-1970

A Conversation with Liliana Porter and Luis Camnitzer (excerpts)

Porter: When I arrived in New York I went to the Pratt Graphic Art Center, which was an open professional graphic workshop on Broadway and 11th street. There were people from all over the world, and compared to Mexico or Argentina, the place was very high-tech. In Buenos Aires you had to buy your own plates and polish them, make your own varnish; in New York everything was ready to use. I began to make large prints and to experiment. Luis was there, on a Guggenheim grant, making woodcuts.

[Camnitzer moved to New York and Lived with Luis Felipe Noe]

[See also Marta Minujin (part of the workshop) - esp. her drawing The Transformation of the Statue of Liberty into Something Edible]

Marta Minujin, The Transformation of the Statue of Liberty into Something Edible, 1980

The story of Julian Firestone, the dentist, who provided the workspace to Porter and Camnitzer:

Porter: During the gallery opening [Porter show at Van Bovenkamp] this American man approached me saying that he had just gotten divorced and that he had an apartment with an electric press in the Village, in Washington Square Park. He explained that since he was a dentist, he wasn't home during the day and could give me the key so that I could work there...The press was in the living room, the acid in the main bathroom. We cleaned it up. Firestone arrived at 8pm every day, and we would help him with his prints. One day he said that the apartment was too uncomfortable, and he rented a big loft. The three of us went to the new place. It was an incredible space in the Village that had been a print shop, so it was well equipped, with big tables and a fireplace; it was fantastic! We didn't have any money to pay for it, so Luis came up with the idea of starting a school there.

CAMNITZER: It was a big space, about 49 x 26 feet. In the back there was an apartment. Later Firestone moved there, which created problems since his personal life sometimes interfered with the activities of the studio.

WTF?

On how teaching was organized:

PORTER: Although we had groups of students in the studio, the focus was always on an individual basis according to each student's skill level. Some of them needed to deepen their analytical skills, others needed to resolve or fine-tune technical issues, while others were artists with well-developed ideas who only needed guidance in using a medium that was unfamiliar to them. Some people did not need a teacher and simply paid by the hour to use the workshop.

CAMNITZER: We discussed all things as a group, but each of us worked on individual pieces. All three of us discussed the work for MoMA and it belonged to all of us. Typically, it was Jose who chose the typeface for the piece. We didn't want to be considered as Conceptual artists, and we also didn't really like MoMA, but at the same time, we understood that it was artistic suicide to not accept [the invitation to participate in the exhibition]. After a long discussion we had this idea that forced the museum to pay for what hopefully would be a huge mailing that we thought might prove very costly to the museum. We don't know how much it cost to send all the announcements, but it looks like the museum overcame it and is doing very well. We did not want to be catalogued as conceptualists; the question of denominations was a formal question. Our concern was not to accept reductionisms. We were more interested in reaching the maximum output with the minimum input. The only way to accomplish this was to use the dynamism of the context, so we decided to promote the notion of "contextual art" rather than "Conceptual art."

MAIL ART

Years later Camnitzer and Porter lived in the same town as Ray Johnson (Locust Valley, Long Island) - they shared the same mail carrier. They made sixteen mail exhibitions. The last one that was sent was Constellations:

CAMNITZER: The last mail exhibition I sent was Constellations, maps of the sky on which I connected the stars in arbitrary geometric shapes. I mailed them to observatories, so that they'd register them in official celestial maps, but they never replied.

Much I have excerpted from various sources.

Please note that I do not own the copyright to most of the texts, images, or videos.