RUDOLF II

Rudolf II and His World: A Study in Intellectual History 1576-1612 by R.J.W. Evans

[Introduction]

Rudolf (1552-1612) remains a strange fugitive figure (the dramatist Grillparzer’s portrait of Rudolf)

Three Rudolfs: 1. the feeble, unstable, and impoverished monarch who began his reign by succeeding to a glamorous political inheritance but ended it a prisoner in his own castle, powerless in the Empire, evicted from Austria and Hungary, deposed even in Bohemia, where he was forced to endure the coronation tumult of his detested brother; 2. The second Rudolf is a great Maecenas, the protector of the arts and sciences, of Arcimboldo and Spranger, Kepler and Tycho Brahe (Maecenas – cultural minister at the time of Octavian); 3. The third Rudolf is different again, and seemingly much less edifying. He is a notorious patron of occult learning, who trod the paths of secret knowledge with an obsession bordering on madness.

Universalist striving of the age – preservation of the mental and political unity of Christendom, to avoid religious schism, uphold peace at home, and deliver Europe form the Ottoman menace / The decades around 1600 saw a broader cultural change: the decline of Latin Humanism and the rise of Baroque, the sinking of an old world-view and the beginning of the seventeenth-century intellectual revolution / They believed that the world of men and the world of nature were linked by hidden sources of knowledge, and that the problems of alchemy, astrology, or the Hermetic texts were proper subjects for learned investigations / The stability of Central Europe and of Bohemia in particular, was thus being undermined on two levels: by the breakdown of an inherited political harmony which issued in the first total European war, set in motion through that defenestration from the royal palace in Prague; and by the decline of a scheme of mental harmony under attack from narrower empirical scientific ideas.

The conflict which played itself out in the Habsburg lands during those years was a political reflection of the whole intellectual confrontation between acceptance of nature and domination over it.

. . .

[Chapter 1: The Habsburgs, Bohemia, and the Empire]

The history of the Holy Roman Empire from the Peace of Augsburg to the Defenestration of Prague has traditionally been seen as the uneasy prelude to a holocaust of hitherto unparalleled violence and destruction.

cuius regio eius religio – Whose realm, His religion / for the first time ‘parties’ began to emerge on confessional lines – a weight of particularism / The background to this complicated picture of superficial calm but inexorable rising tensions was a growing lethargy and retreat from practical affairs – and age of occult pursuits, exotic private collections, princely stifling of free endeavour, impractical dreams, and wild social intolerance.

the confession, confessions, confessing, I confess, to confess

. . .

To a large extent the political history of Central Europe in the second half of the sixteenth century has always been written in terms of the war which followed / The turning-point was more nearly the years around 1600 than a single hectic act of rebellion in 1618 which was merely the climax of more than decade of desperate uncertainty – The underlying change was ultimately a decisive factor in the failure of Rudolf’s own life (pp. 9)

centripetal and not yet centrifugal

All the major ruling families of Europe developed during the Renaissance period their characteristic symbolism, which came to represent a kind of apotheosis of their own claims to power, and the later sixteenth century with its cult of the emblematic and allusive made full use of such iconography.

the war of the pamphleteers

The notorious debate of the sixteenth century was, of course, over Machiavelli.

Rudolf II moving his government from Vienna to Prague in Bohemia during the first years of his reign.

. . .

[Chapter 2: The Politics of Rudolf]

. . .

melancholy / “Rudolf has, however, ruined everything by taking up the study of art and nature, with such increasing lack of moderation that he has deserted the affairs of state for alchemists’ laboratories, painters’ studios, and the workshops of clockmakers. Indeed he has given over his whole palace to such things and is using all his revenues to further them. This has estranged him completely from common humanity: ‘Disturbed in his mind by some ailment of melancholy, he has begin to love solitude and shut himself off in his Palace as if behind the bars of a prison.” (pp 45)

It is doubtful whether Rudolf was in fact ever mad in any serious technical sense; certainly not for longer than brief intervals, as for a time during 1600 or 1606, while much hinges on the meaning which contemporaries attached to words like “melancholy” and “possession“

. . .

Amid the complexity of Rudolf’s own environment there were three abiding influences, and these must be briefly isolated, since he was always very conscious of them: the hereditary background, the ‘Spanish humour’, and the court circle of his father Mazimilian II.

(schizoid psychopaths in his family, his don, Don Guilio, syphilis)

Time spent in the Spanish court: upon his return a stiffness of attitude, pride, religious dogmatism / auto-da-fé, the act of public penance (burning at the stake) / he dressed in Spanish fashion, spoke Spanish formally for preference, placed great trust in advisers with Spanish connections / but also a revulsion against Spanish pretensions

some knowledge of Czech / the failure of successive Habsburgs to learn the main language of their Bohemian subjects

a universality mission

illness / marriage / lack of a successor

Symbolic pageantry in the funeral of Maximillian II – the Castrum Doloris – the Knighthood of the Golden Fleece (the fleece of -Who, to carry off the fleece of Colchis, was willing to commit perjury – or the Fleece of Gideon – proof of God’s will in the fleece) / “I will have no other”

Further evidence that Rudolf lavished much attention o the prestige of the dynasty is provided by his reconsecration of the tombs of all of the Emperors buried in St. Vitus. In 1590 he had their graves opened and the coffins placed in an elaborate white marble mausoleum at the center of the Cathedral.

The Bohemian coronation of Rudolf in the Cathedral of St. Vitus within Prague Castle on 22 September 1575 was a great spectacle, deliberately contrived, as the records show, to dazzle and impress the assembled people. For it the historic Wenceslas crown was used, which occupied an important place in the ceremonial of the later sixteenth century.

. . .

[Chapter 3: The Religion of Rudolf]

. . .

Maximilian II refused the last sacrament, because to receive sub una specie was sinful and to receive sub utraque would offend his family / of Rudolf – “Not only did his Majesty not confess, he did not even display any sign of contrition”

Rudolf was persistently trying to maintain a position which was free of both sides, but in doing so he necessarily offended both.

. . .

[Chapter 4: The Habsburgs, Bohemia, and Humanist Culture]

. . .

The revival of botanical studies in the sixteenth century formed one aspect of a changing attitude to the natural world: the urge to classify it, a striving not yet divorced from the sense that it was a world which men belonged, as members of a consistent chain of influences.

There also developed, especially in Prague, a growing fashion for contrived gardens…the Stag’s Ditch, the Paradise Garden, and the rest with their rare and peculiar plants, menageries, and flowers set to represent the personal symbol of the Emperor.

Joannes Sambucus (Janos Zsamboky) b. 1531 – best known as an emblematist (was the court physician under Maximilian II). His emblem book was one of the most prized and widely circulated volumes to come from Plantin’s presses (Antwerp, one of the focal centers of the fine printed book of the 16th century – the Plantin-Moretus Museum) and it exercised large influence, both on the compilers of the same genre, and on the literary world in general, even Shakespeare / the symbol could possess deeper meaning as an embodiment of the reality of nature / Rudolf maintained Sambucus’s famous library after his death (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sambucus)

historiography and the cult of the antiquarian

The Latin poem in Rudolfine Prague – the elegy, satire, epithalamium (poem written for a bride on her way to the marital chamber), and carmen gratulatorium (a wedding song), the encomium (praises something or someone highly) and oration for funeral, victory or distinguished guest

. . .

[Chapter 5: Rudolf and the Fine Arts]

. . .

a passion for glyptics – the cutting and engraving of gems (1. a love of rare and exotic artistic material, 2. the opportunity for a conscious display of skill, 3. the reflection of a belief in talismans and the astral power of stones)

“the art of Rudofine Prague was essentially a revelation of mystery, whether through the medium of the canvas, or the manipulation of stones, or the alchemical and Cabalist ‘arts'”.

Mannerism – uniform style of courtly elegance and a highly artificial mode of expression – contrived anti-Classicism / an international and far-reaching style / a culmination of the whole post-Renaissance process of developing maniera: panache and self-conscious artistry / Rudolfine Mannerism based itself more or less consciously on both the art-theory of the North Italian school and the academic mentality of the later sixteenth century – contacts between Florence, Milan, Venice, and Prague were close (ex. Arcumboldo – court artist / the Prague Mannerists enjoyed as direct patron the sovereign himself, and their choice of subject-matter reflects Rudolf’s own inclinations – The Emperor employed and encouraged them personally, approved and criticized their work, on occasions even participating in their activities.

new observations of nature, large play with allusion, tendency toward eroticism, employment of symbol as means of communication

Guiseppe Arcimboldo (1527-93)

Batholomaeus Spranger

preoccupation with suggestive, even indecent subjects is typical of Rdolf and the last two decades of the sixteenth century – a feature of late Mannerist art (stop at 169)

________

Rudolf II’s Kunstkammer was one of the most diverse of its times. Plundered in 1648 by Swedish forces when Prague was captured, only parts of it are today extant in the Vienna collections.

The plunder from the castle at Prague included 470 paintings, 69 bronze figures, several thousand coins and medals, 179 objects of ivory, 50 objects of amber and coral, 600 vessels of agate and crystal, 174 works of faience, 403 Indian curiosa, 185 works of precious stone, uncut diamonds, more than 300 mathematical instruments and many other objects.

this collection was not a gallery in the modern sense but rather united works of art with exotic animals, minerals, lapidary work and much more besides. It too was intended to represent an image of the universe. Rudolf’s huge collection needed a corresponding amount of space, and rooms in the castle at Prague were adapted to house it. The emperor collected on an unparalleled scale: when his agents, continually scouring Europe for new objects, were unable to acquire certain objects, he had them copied. Workshops at his court produced art objects. He had an especial predilection for lapidary work. This interest was of a piece with Rudolf’s pansophical view of the world that regarded everything, including the physical world of phenomena, as part of a universal system.A showpiece of the collection and of the goldsmith’s art that was patronized by the court was the imperial dynastic crown.

Rudolf was also fascinated by natural phenomena, and commissioned his own court artists to produce paintings of natural objects and animals.

In the inventory covering the years 1607 to 1611 Daniel Fröschl (1563–1613), court painter and administrator of the imperial collections, listed natural objects including chameleons, crocodiles, fish, a bird of paradise and many other creatures. If a stuffed specimen was not to be had, Rudolf had the animal in question painted. There were even images of unicorns, dragons and mandrakes in his collections.

The Magic Circle of Rudolf II

The Feast of the Rosary (1505) – Durer / brought from Venice and over the Alps

cujus regio ejus religio / who owns the region owns the religion

Maximilian state entertainment spectacle of 1570: “Here was Mount Etna, from which sparks and smoke emanated, ravens and other birds flew, fiery tubes shot out. As well as Perseus. holding the head of a Gorgon and sitting astride the winged horse Pegasus, it was possible to behold a lion in a wooden cage. Apart from that and other spectacles a live elephant, a huge creature the like of which has never before been seen in these lands, was led into the square, and Porus, King of India, was seated thereupon…”

When Rudolf came into the world he was small and sickly and not expected to live. Rather than finding comfort in his mother’s breast, he was plunged into the carcass of a freshly killed lamb – then when it cooled, into the carcass of another, and yet another, rushed from an adjoining butcher’s slab.

autos-da-fé, the act of public penance (burning at the stake)

Don Carlos – fell down a flight of stairs – trepanation (drilling to let out the evil spirits)

Trust no one, listen to everyone, decide alone

El Escorial contained more than 6,000 holy relics, including an alleged nail from the True Cross, a hair from Christ’s beard, a thorn from his crown and part of a handkerchief used by the Virgin Mary and still stained with her tears.

Rodolpho di poche parole / Rudolf of few words

An ominous celestial event confirmed for many the growing disharmony in Europe. Comets had long been considered omens of war, plague and famine. But then a new tailless start – a supernova – appeared in the Cassiopeia constellation in 1572, the very year that Rudolf had been crowned king of Hungary. It suddenly shone brightly and then gradually changed colour and eventually disappeared from the sky during 1574. It was observed by the court astronomer Tadeas Hajek in Prague and by the aristocratic Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe in his observatory on his island called Uraniburg (City of Heavens) / Since the appearance of the star implied that the heavens were not perfect at all, as the traditional Aristotelians claimed, Brahe interpreted the celestial drama as a sign that the world would perish by fire.

Despite being born under the sign of Cancer, he even adopted Augustus’s zodialogical sign of Capricorn, depicted by a creature with the tail of a fish. This symbol was placed on many works depicting Rudolf as the new Augustus as were the world Astrum fulget caesareum / the imperial star shines

As for the Habsburg treasures and works of art, Rudolf was determined to try to reacquire them from the members of his family to whom they had been bequeathed. He particularly coveted two talismans which had been given to his uncle Ferdinand of Tyrol: an Ainkhuern, allegedly the horn of a unicorn which had magical powers, and an ornate agate cup which had been pillaged from Byzantium during the 1204 crusade and which was said to be nothing less than the Holy Grail.

“Man makes his destiny by his own courage…You also have received some gifts from God, and that is why you must fight like your ancestors. You fear losing your States and your peoples?”

The principal decision of the parliament at Augsburg was to adopt the new Gregorian calendar which replaced the old Julian calendar, which was twelve days out of kilter with the cycle of the sun. Pope Gregory XIII accepted the new calendar and chose the first day of January rather than Easter as the beginning of the New Year. At the parliament, the Catholics accepted the proposal; the Protestants, suspicious of a papal plot, rejected it. One Lutheran prince saw it as a sign of the impending Apocalypse / “The essential is that the calendar is good. Its origin does not matter.”

. . .

1583 established Prague castle as the imperial seat /situated in the Bohemian basin created millions of years previously by a meteorite /”I see a great city whose fame will touch the stars” / prah in Czech is threshold – Praha

Jan Huss : (trial -1415) Hus declared himself willing to submit if he could be convinced of errors. This declaration was considered an unconditional surrender, and he was asked to confess:

- that he had erred in the theses which he had hitherto maintained;

- that he renounced them for the future;

- that he recanted them; and

- that he declared the opposite of these sentences

An Italian prelate pronounced the sentence of condemnation upon Hus and his writings. Hus protested, saying that even at this hour he did not wish anything, but to be convinced from Holy Scripture. He fell upon his knees and asked God with a low voice to forgive all his enemies. Then followed his degradation — he was enrobed in priestly vestments and again asked to recant; again he refused. With curses his ornaments were taken from him, his priestly tonsure was destroyed, and the sentence was pronounced that the Church had deprived him of all rights and delivered him to the secular powers. Then a high paper hat was put upon his head, with the inscription “Haeresiarcha” (meaning the leader of a heretical movement). Hus was led away to the stake under a strong guard of armed men. At the place of execution he knelt down, spread out his hands, and prayed aloud. It is said that when he was about to expire, he cried out, “Christ, son of the Living God, have mercy on us!”

The executioner undressed Hus and tied his hands behind his back with ropes, and bound his neck with a chain to a stake around which wood and straw had been piled up so that it covered him to the neck. At the last moment, the imperial marshal, Von Pappenheim, in the presence of the Count Palatine, asked him to recant and thus save his own life, but Hus declined with the words “God is my witness that the things charged against me I never preached. In the same truth of the Gospel which I have written, taught, and preached, drawing upon the sayings and positions of the holy doctors, I am ready to die today.” He was then burned at the stake, and his ashes thrown into the Rhine River.

Anecdotally, it has been claimed that the executioners had some problems scaling up the fire. An old woman came closer to the bonfire and threw a relatively small amount of brushwood on it. Hus, seeing it, then said, “Sancta Simplicitas!” (Holy Simplicity!) This sentence’s Czech equivalent (“svatá prostota!”, or, in vocative form “svatá prostoto!”) is still used to comment upon a stupid action.

. . .

The “Golden City”, larger at this time than London or Paris

The Prague astronomical clock, or Prague orloj: (Large astronomical clock in the main square, made in 1410, which indicated the time of day in Babylonian time and Old Bohemian time. The clock, which still exists, also depicted Ptolemy’s model of the universe with the Earth at its center and charted the movements of the sun and moon through the signs of the zodiac. Moving figures were added in 1490. On the hour, the twelve Apostles appeared in windows before figures representing what was considered to be the chief threats to Bohemia at the time: the lender with the money bags; Death, depicted as a skeleton carrying an hourglass and tolling a bell; a Turk shaking his turbaned head; and Vanity admiring his reflection in the mirror. Four other immovable figures symbolized Philosophy, Religion, Astronomy and History (pp 47) / it is the oldest astronomical clock still working

. . .

The order of the Golden Fleece / Rudolf’s investiture in 1585 / a chivalric order of knights dedicated to the defense of the Church / as steady and intrepid in their defense of Christianity as Jason’s Argonauts

Towards the end of his life, when he hardly left his rooms, he would have his favorite horses paraded in front of his windows

Painting placed not on walls, but on ledges, tables, and special stands (could fall off the edge of the earth perhaps)

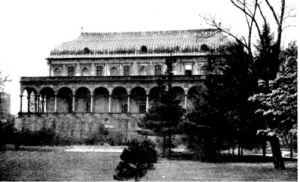

The north wing of the castle with its stables, hall and gallery was joined in the 1590s by the “Long Corridor” (Langer Bau) stretching 100 meters to connect with Rudolf’s private chambers in the new Summer Palace on the south side, facing the city / The corridor housed Rudolf’s famous collections of precious objects on three levels: on the ground floor, his collection of rare saddles and harnesses; on the first floor, divided into four separate rooms, his celebrated Kunstkammer or “Chamber of Art”; on the second floor, more paintings and sculptures / Midway between the north wing and his apartments rose The Bishop’s Tower (also known as The Mathematical or Astronomical Tower) from the flat roof of which the night sky could be surveyed.

In the Powder Tower set in the northern ramparts of the castle, Rudolf established an alchemy workshop and filled it with the latest instruments – vases, tubes and stills – produced by his glass blowers and by the most competent alchemists

Gardens / a heated walled aviary, which housed rare birds – parrots, birds of paradise a dodo / a wooden menagerie (Lion’s Court) – tigers, wild cats, bears and wolves / Tycho Brahe, Rudolf’s court astronomer, declared that since they shared similar horoscopes they would suffer a similar fate. The prophecy proved to be accurate: when the lion eventually died, Rudolf locked himself in his chambers, refusing all medicine and help, and died three days later.

The Royal Gardens – planned in the Italian style / apples, palms, olives, cedars, as well as shrubs and flowers / some were formed into individual letters, while others took the shapes of whole sentences / In a raised parterre brightly colored flowers against green grass formed the letters of Rudolf’s talismanic device ADSIT, which probably stood for a Domino salus in tribulatione – In trouble deliverance comes from the Lord – paraphrase of Pslam 36:39 / ADSIT is also the Latin for “May He be Present” / also a maze – pilgrim searching for the celestial city (but also in mythology – as a defense mechanism?) / the garden as living encyclopedia – also area for alchemical experiments / the sacred tulip (pp 54) / also a Belvedere (the Summer Palace)

Much I have excerpted from various sources.

Please note that I do not own the copyright to most of the texts, images, or videos.