TRISHA BROWN

TRISHA BROWN: DANCE AND ART IN DIALOGUE, 1961-2001

GRAVITY'S RAINBOW by Maurice Berger

Man Walking Down the Side of a Building (April 1970)

"In a kind of parallel to Brown's gravity-bound, antisymbolic approach to the dancer's body, they [artists of the 1960s and '70s] relieved the art object of the task of representing other objects or things in the world, thus avoiding psychological or narrative references that would get in the way of the spectator's phenomenological exploration / Brown has always encourages this empathic relationship, eschewing the kind of stylized, theatrical movement that distances dancer from audience. She breathed new life and meaning into ordinary movements, turning simple actions like sitting, running, or putting on one's clothes into fluid, exuberant variations of a theme."

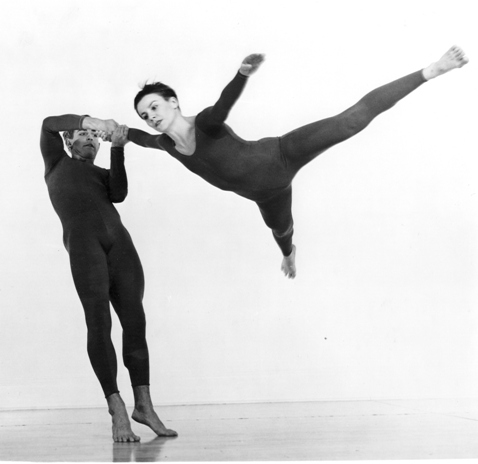

"To watch one of Brown's dances is to learn much about one's own body, to understand its energy, its expressive potential its limits. If the choreographer has created an aesthetic that allows her to explore the 'further access to her [own] physicality,' she has done so with the full intention of inviting her audience along for the ride."

"trillium" / [first dance of her own that she performed solo in public]

TRISHA BROWN, U.S. DANCE, AND VISUAL ARTS: COMPOSING STRUCTURE by Marianne Goldberg

"Her formal training in modern dance began in 1954, when she enrolled at Mills College in California. As her choreography has evolved over such a substantial span of time, it has coalesced into distinctive phases of work, each with similar compositional pursuits / Brown's formal training at Mills in a top art technique - that of Martha Graham and Graham's choreographic mentor, Louis Horst - led her initially to compose in that tradition."

[FROM THE BIOGRAPHY OF TRISHA BROWN] After graduating from Mills in 1958, Brown taught dance at Reed College in Portland Oregon before participating in a six-week workshop with Ann Halprin in the summer of 1960. Other participants in the workshop included Yvonne Rainer, Simone Forti and June Eckman. Moving to New York City in 1961, Brown joined Robert Dunn's dance composition class at the Merce Cunningham studio. It was in Dunn's class that Brown learned about John Cage's chance procedures. Of this experience, Brown noted that she "understood for the first time, that the modern choreographer has the right to make up the WAY that he/she makes a dance" (see Brown's "How to Make a Modern Dance When the Sky's the Limit" in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001).

"In the sixties, Brown experimented with non-formal movement and instinctive physical responses to Dunn's assignments, as well as a blend of the conceptual and physical . . ."

During the 1960s, Brown participated in other fields of experimental art, including music, poetry, and the visual arts. In the late 1960s, Brown began to make drawings, a practice she has continued.

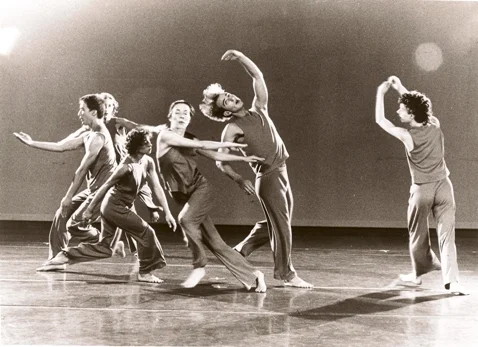

In 1970, Brown founded the Trisha Brown Dance Company with Carmen Beuchat, Caroline Goodden and Penelope [Newcomb]. The Company toured the United States and Europe performing works such as Accumulation (1971), a signature solo piece for Brown in which she "unfolds increment by increment—from thumb to wrist, wrist to elbow, elbow to shoulder, shoulder to neck, hip to knee," exposing "the cognitive challenge of performing, showing the dancer and the body in the course of thinking, not merely gesturing in space, and offers the satisfaction of watching a composition materialize according to an indissoluble unity of intent and action: the body’s vocabulary as a movement language" (Susan Rosenberg, Accumulated Vision: Trisha Brown and the Visual Arts).

Brown regularly performed outside of traditional theater venues, choosing instead to perform in lofts, galleries and outdoor spaces, such as rooftops, parks, streets, churches, parking lots and plazas. When using conventional proscenium stages, Brown tried to disrupt the "window" or frame around the dancers and de-emphasize the customary hierarchical relationship of both the stage and the body, where the center is more important than the periphery. "Brown reinvents the body as a field of equal places, with varying centers. Actions can be initiated form any place at any time" (Marianne Goldberg, see Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001).

In Son of Gone Fishin' (1981) and Newark (Niweweorce) (1987), Brown, in collaboration with Donald Judd, created works that decentralized the stage, developing allover compositions.

A FOND MEMOIR WITH SUNDRY REFLECTIONS ON A FRIEND AND HER ART by Yvonne Rainer

"Her dancing, from now on, in its rootedness in idiosyncratic personal/physical history, detachment from musical and narrative cues and refusal to conflate emotional expressivity with recognizable mimesis, would push her toward nothing less than rewriting the terms of choreographic expression and its previous manifestations." (see "A Fond Memoir with Sundry Reflections on a Friend and Her Art," by Yvonne Rainer in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001).

BROWN IN THE NEW BODY by Steve Paxton

"Trisha and her friends Simone Forti and Yvonne Rainer were some of the few dancers I knew in those days who improvised. The rest of us tended to create structures in which our rigid legs and pointy toes were accepted as the natural way for a dancer to exist . . . What were they doing? They were constructing milliseconds with their sensations and their ideas in a heady mix which swirled through time catalyzed by our complicity, our viewing. We saw anew. What a relief . . . Trisha Brown's accomplishment is to express the new body, surmount the system, and beat the dictates of those who have no idea of their own body, or anyone's." (see "Brown in the New Body" by Steve Paxton in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001).

BIRD/WOMAN/FLOWER/DAREDEVIL by Hendel Teicher

"In Brown's collaborative process, she encourages and celebrates complexity, allowing for unpredictable events to surface. Each of these projects is a way towards making chaos visible."

INTRODUCTION TO TRISHA BROWN'S CHOREOGRAPHIES 1979-2001 by Hendel Teicher

"With the same collaborative spirit that marked her work from the moment of her arrival in New York in 1961, Brown embraced the theater as an interdisciplinary environment. Brown made dances that allowed, and even required, her dancers to talk; she unceremoniously broke the silence of the technicians of modern dance. Beginning in 1979, Brown's creative sensibility for dialogue expanded in a new way to the visual arts when she invited Robert Rauschenberg to design the set and costumes for Glacial Decoy . . . Inviting Rauchenberg and, later, other painters, sculptors, and stage designers - Fujiko Nakaya, Donald Judd, Nancy Graves, Roland Aeschlimann, and Terry Winters - to join her in collaborative creation of a work for the stage became a central feature of her practice" (see Introduction to Trisha Brown's Choreographies 1979-2001 by Hendel Teicher in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001).

SON OF GONE FISHIN' (1981) / NEWARK (NIWEWEORCE) (1987)

Son of Gone Fishin' (1981)

CHOREOGRAPHY: Trisha Brown

CYCLE: Unstable Molecular Structure

LENGTH: 25 minutes

MUSIC: Robert Ashley, "Atalanta"

MUSIC PERFORMANCE: Robert Ashley with Kurt Munkacsi; live only at first performance

VISUAL PRESENTATION: Donald Judd

SETS: a series of five drops upstage, moving through a variety of positions by Donald Judd

COSTUMES: Judith Shea, based the final color scheme of the costumes on on Donald Judd's green and blue set

LIGHTING: Beverly Emmons

ORIGINAL DANCERS: Eva Karczag, Lisa Kraus, Diane Madden, Stephen Petronio, Vicky Shick, Randy Warshaw

US PREMIERE:

BAM Opera House, Brooklyn, NY, October 16, 1981

WORLD PREMIERE:

Festival d'Automne à Paris, Theatre de Paris, Paris, France, November 13, 1983

"The choreography was a 'doosey.' In it I reached the apogee of complexity in my work. The infrastructure of the piece was related to the cross-section of a tree trunk. ABC center CBA. Complex group-forms of six dancers were performed first in the normal direction and then in retrograde. Bob Ashley gave us a little library of different tapes to carry with us on tour. The dancers randomly chose which music we would use each performance. Something like having the band along with us" (Trisha Brown, see Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001)

"After working for a decade or so, I noticed that my dances tended to cluster together in cycles. I take a compositional subject that intrigues me, work on it over two or three pieces until I have my answers, and then I move on. The early sixties were about discovery in the realm of improvisation versus form. I cam back to that subject in the Unstable Molecular Structure cycle of work, Opal Loop/Cloud Installation #75203 (1980), Son of Gone Fishin' (1981), and Set and Reset (1983). All of these dances were created by the dancers through a complex process of improvisation, repetition, and memorization of the aleatoric enactment of phrases according to instructions provided by me. During the choreographic process, I stepped out of the dance to view the work as it evolved, to make editorial decisions" (see Brown's "How to Make a Modern Dance When the Sky's the Limit" in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001).

Newark (Niweweorce) (1987)

CHOREOGRAPHY: Trisha Brown

CYLCLE: Valiant

LENGTH: 30 min.

MUSIC: Peter Zummo, from sound concept by Donald Judd

VISUAL PRESENTATION: Donald Judd

SETS: Donald Judd

COSTUMES: Gray unitards by Donald Judd

LIGHTING: Ken Tabachnick with Judd's directive to be "plotless"

ORIGINAL DANCERS: Jeffrey Axelrod, Lance Gries, Irene Hultman, Carolyn Lucas, Diane Madden, Lisa Schmidt, Shelley Senter

WORLD PREMIERE:

CNDC/Nouveau Theatre d'Angers, Angers, France, June 10, 1987

US PREMIERE:

City Center, New York, NY, September 14, 1987

"During the making of this dance, one of Trisha Brown's production assistants would yell out 'new work!' to announce onstage rehearsal time for the yet untitled piece. Brown heard this prompt as 'Newark!' which she likened to the bellowing of a train conductor, and made it the main title of the new dance. She then looked up the word in the Encyclopedia Britannica, and found that the original name for Newark, England, was 'Niweweorce,' a term that was used around 1055 or earlier. Brown was taken by the words and sounds that could be found by extrapolating from this obsolete name - wow, wew, new, weorse [as in 'worse'], and so on. Niweweorce became the subtitle of the piece" (see Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001)

The set design for Newark (Niweweorce) was a further development of the stage design Judd created for Son of Gone Fishin' in 1981. Whereas the drops were used upstage in Son of Gone Fishin', in Newark they use the entire stage.

"During the ten years I danced with Trisha, I rarely repeated the same movement twice; a reference to another work was the exception to the rule. The rule being: explore new territory to create, beginning at the foundation - the movement. With a passion for geometry, respect for the body's organic function, and an acute attention to detail, Trisha Brown has pioneered her own movement vocabulary." (Carolyn Lucas, one of the original dancers in Newark (Niweweorce), see Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001)

"The second piece in this new cycle [The Valiant Cycle] was Newark (Niweweorce) (1987), with set, costumes, and music by Donald Judd, a sculptor I had collaborated with to make Son of Gone Fishin'. In both instances that we worked together, Judd brought his Minimalist aesthetic to my stage. A residency at the Centre National de Danse Contemporaine in Angers, France, gave Don and me, plus Peter Zummo, music production, and Ken Tabachnick, lighting design, the crucial time on stage to choreograph with the set and lights every day, six days a week, for six weeks (see Brown's "How to Make a Modern Dance When the Sky's the Limit" in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001).

"Don's stage design comprised five proscenium-size drops in the three primary colors plus brown and another shade of red. They split the stage into sections forming corridors, which could alternately block and reveal the dance. Don devised three separate mathematical systems to determine what drops, in what order, would come in where and for how long."

"The music which consisted of nonreferential sounds found by Peter Zummo, was on yet another system of all its own. I had unwittingly allowed Judd to usurp the choreographer's territory of time and space. He would cut off a dancer flung high in an arc, or confine us in a narrow strip on the downstage light line, five feet deep and forty wide. My choreographic solution was to visually design the dance into the motional elements of the set, albeit adapting a few aspects to my favor. Why did I put up with it? Too late to change for one, but remember that abstract modern dance, unfettered by story and music, is, necessarily, in search of a logic or rationale to reduce the proliferation of options that hang around winking at us. The Newark set did impose tough dialogues and severe internal limitations, but it also delivered a spatial and temporal score that forced invention and resulted in one of the most striking pieces in our repertory" (see Brown's "How to Make a Modern Dance When the Sky's the Limit" in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001).

+ DONALD JUDD AND TRISHA BROWN

(Interview with Regina Wyrwoll, October 4-5, 1993, Chinati Foundation Newsletter, vol. 14)

"It was very difficult for me to get started with music. I was helped a little bit, or a lot, by a composer in New York named Peter Zummo, who has perfectly clear ideas of his own. he put away his ideas to help me with mine, which was very nice. He was working with Trisha Brown. What I needed were sounds—I just wanted sounds. I didn’t want them to be associated—I didn’t even want them to be from instruments, I didn’t want them to be natural—I just wanted a lot of sounds. and then a great range of volume, of density, of all the possibilities. And then I wanted to be able to cut it up into parts where you hear one, then one stops and you hear the other with lots of subdivisions"

"If you don’t want to embrace the proscenium stage, then why go along with the circumstances — this was a little bit of a Gesamtkunstwerk, actually. Why go along with the circumstances where the dancers have no reaction to the set, the set has no effect upon them? With the set I made, you would suddenly have a very shallow space for people on one side, and a very deep space with people on the other side, and all sorts of different circumstances — dancers would have to deal with that. or the players in a play."

Much I have excerpted from various sources.

Please note that I do not own the copyright to most of the texts, images, or videos.