On Knowing & Not: Jean-Baptiste Bernadet and John D'Agata

Jean-Baptiste Bernadet, On Knowing & Not

A text by John D’Agata excerpted from About a Mountain 12/16/2012

Karma, New York, 2013

10.5 x 8.4 inches (26.67 x 21.33 cm)

128 Pages

Edition of 1,000

In his introduction to The Lost Origins of the Essay (2009), John D’Agata describes the fact-based writing of the burgeoning, now six thousand year old, Sumerian civilization as “the ceaseless shapeless clattering of the who-what-when-where-why.” Arguing that the gods were displeased with the Sumerian’s noisy, commercially driven, fact-gathering behavior, D’Agata writes that the gods “dissolved everything back into mud” rendering this desert between two rivers “indistinguishable from the nothing it has emerged from.”

D’Agata proposes a different origin story for the Essay, one that begins in Sumer, but is “not propelled by information, but one compelled instead by individual expression—by inquiry, by opinion, by wonder, by doubt.” D’Agata’s 2010 book About a Mountain positions itself within this lineage, a lineage not of data and facts, but of the pursuit of ideas, with all its attendant attempts.

In a different desert, thousands of miles and years from Sumer, these fundamental questions of who-what-when-where-why (with the addition of how) were again asked, but to ends quite different from trade, commerce, and accounting. In 2011, D’Agata and painter Jean-Bernadet Bernadet lived in the rural desert town of Marfa, Texas, each as participants in residencies related to their respective fields. Upon hearing D’Agata read from his then recently published About A Mountain, Bernadet wrote that he “felt the themes of failure, of attempt, of knowledge, of understanding, of retaining the feelings and trying to understand their meanings which was exactly what I was looking for in painting.” In response, Bernadet, in collaboration with D’Agata, created a 2013 publication which includes the last section of About a Mountain, the section Bernadet heard D’Agata read a few years prior and a large selection of Bernadet’s paintings.

D’Agata’s contribution to On Knowing & Not begins with a question of human survival. Will the human race survive another century, let alone another 10,000 years, the period set by the Energy Policy Act of 1992 relating to the duration needed to protect a repository of nuclear waste? The second number is significant to About a Mountain because of the proposed storage of such waste in Yucca Mountain, the eponymous landform ninety miles north of downtown Las Vegas, the city where D’Agata’s mother chose to move shortly before he began writing his text. The storage of such dangerous material raises the a number of obvious questions. Can the population of the future be protected from the nuclear waste storage facility of today? What language, music or visual signifiers should we use to induce a millennia-spanning regard for the site? And more specifically, could a painting inspire the necessary emotion or communicate the danger?

The United States’ Department of Energy, perhaps assuming that human emotions will remain constant during the next 10,000 years, proposed using Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893), a painting that is currently very well known, on all warning signage for the storage site at Yucca Mountain. For D’Agata, Munch serves as an example, one in an unfathomable amount of possible examples, of the complexity of what it is to know or not know. As D’Agata writes, Munch couldn’t have known, for example, that his childhood friend would one day kill himself. Nor could have known of his eventual hospitalization for a “nerve crisis,” nor the extraordinary number of paintings, prints, drawings and sculptures he would produce in his life. Neither could he have known that in May 2012, The Scream would sell for a record setting $119.9 million, the most expensive artwork ever sold at an open auction to that point. He certainly could not have know that seven decades after his death, some of the world’s brightest minds would consider the efficacy of using one of his paintings as a warning against the extraordinary dangers associated with nuclear waste.

In the seconds before Levi’s jump, did the security officer say, “Hey” or “Hey Kid” or “Kid, no”? Levi was sixteen years old when he drove to the Stratosphere that summer. He had likes and dislikes. He liked going to In-N-Out. He liked a girl named Mary. D’Agata in attempting to understand Levi, his life and his suicide, had tries and pursuits. “I tried to call his parents but their number wasn’t listed,” he wrote. “I tried to go to his funeral but his service wasn’t public.” What was D’Agata’s pursuit? Was it to identify the facts of what actually happened the night of Levi’s suicide? To make the facts firm and sturdy? “Sometimes we misplace knowledge in pursuit of information,” D’Agata writes. “Sometimes, our wisdom, too, in pursuit of what’s called knowledge.” What can be learned from a painting or an essay? Perhaps we will never know what happened the night of Levi’s death. Or why The Scream became “the most recognizable painting in the world” or whether it will remain so. Perhaps the firm and sturdy facts do not hold the weight of time and experience. Perhaps there is only the entangled coexistence of knowing & not knowing.

In 1891, the French painter Paul Gauguin traveled to Tahiti, the largest island in French Polynesia. Formed by volcanic activity, Tahiti was first settled around 200 BC. Expecting a primitive Eden, Gauguin’s desire for a personal paradise was marred by his realization that Tahiti was already populated by European expatriates. Returning to France in 1893, the same year as Munch’s Scream, Gauguin began work on Noa-Noa, an illustrated narrative recounting his two years on the island. He hoped his blending of the textual and visual would help acclimate the French art-world to new themes and techniques he had developed while in Tahiti. “Whereas Munch presented his subconscious themes in terms of bold forms and daringly disturbing images, Gauguin surrounded his with a mysterious light,” wrote art historian Richard S. Field in 1964. “Whereas Munch’s figures overpowered their environment or projected their psychological contents onto it, Gauguin’s were more subtly united in their settings. And where Munch’s personages were the victims of expressionistic distortions, those of Gauguin, deriving so often from traditional sources, were endowed with a certain ceremonial classicism.” Noa Noa’s text and accompanying ten woodcuts share thematic concerns. Both elements reflect Munch’s desire to allegorize Tahiti and the Tahitians, as well as the life cycle of birth and death. In the woodcut Te Faruru one sees a couple entangled in each other’s arms in a sensuous depiction of sexual maturation. Although the woodcuts do not correspond directly to the text, Gauguin provides the reader with enough visual information to answer with general confidence who-what-when-where-why-how. This narrative ease is what perhaps allowed for Noa-Noa, meaning “fragrant scent,” to easily be appropriated in the mid-1950s as the name of a perfume for a women seeking her own sensual “personal paradise.”

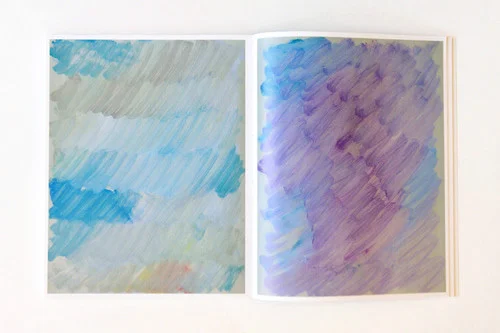

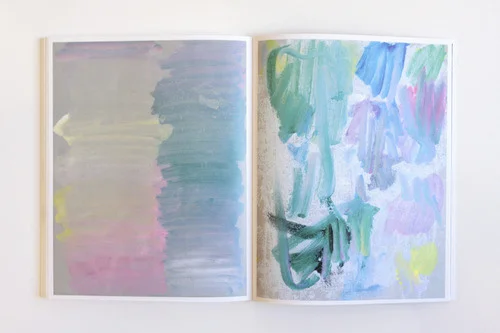

To arrive at the core of an issue, 1st century BC rhetorician Hermagoras of Temnos proposed a system of seven circumstances: Quis, quid, quando, ubi, cur, quem ad modum, quibus adminiculis (Who, what, when, where, why, in what way, by what means). D’Agata organized the chapters of About a Mountain by the abbreviated version of this system, who-what-when-where-why-how. Yet, the abstract and indefinite qualities of Bernadet’s paintings for On Knowing & Not eschew the desire for information gathering. Unlike Gauguin, the allegories in Bernadet’s paintings, if they exist at all, are suggestive and pliant. Unlike Gauguin, Bernadet’s paintings do not provide answers to the questions who-what-when-where-why-how, but instead destabilize the belief that by asking these questions one can arrive at a factual understanding of an experience. Unlike Gauguin, the paintings reject narrative ease, for perhaps any true narrative is never easily determined. The questions who-what-when-where-why-how, as Bernadet suggests, are like his paintings, both abstract and indefinite. “They are not an answer,” Baptiste writes, “they do not represent a solution.”

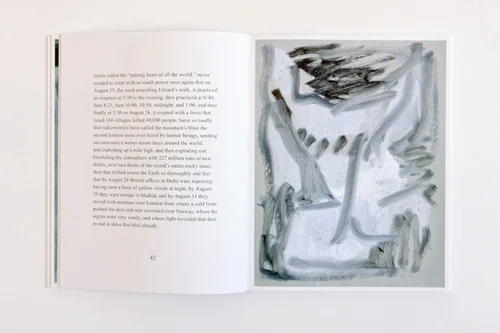

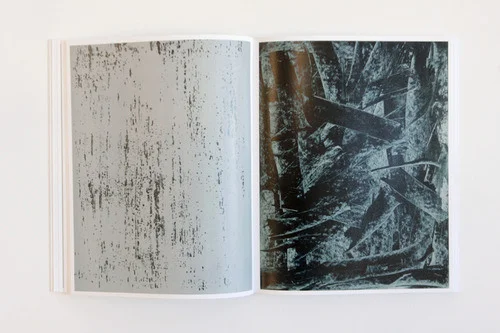

Bernadet’s 12 x 16 paintings on paper, from which the illustrations for On Knowing & Not were reproduced, are present and diverse. Their size and number intimate a consistent focus of attention without devolving into redundancy. Wholly abstract, these non-narrative paintings exhibit a diversity of formal techniques, gestures, and color combinations. Viewed all together, they reflect an abundance of attempts. As a series, the paintings reject fixity. Although unified by their size and material base, each is a separate endeavor, a word all its own. As Bernadet writes, “I consider my paintings as words, creating sentences when I hang several paintings in a show, and I consider the whole body of works I made as a book in progress.” In On Knowing & Not, Bernadet paints the essay. “As a writer of essays,” D’Agata writes, “my interpretation of that charge is that I try—that I try—to take control of something before it is lost entirely to chaos.”

Bernadet’s paintings are not chaotic, but reflective of temporal and physical fluxes. They demonstrate shifts between stillness and fluidity and suggest changes in states of matter, vacillating between solidity and liquidity. A number of the paintings display a gaseous quality, with areas resembling pockets of air surrounded by seemingly fluid expanses of paint on the surface of the paper. At times appearing geologic, the paintings reflect the qualities of a bisected volcanic rock. Of the paintings, Bernadet writes, “These fragile, instant and almost unconscious paintings are adding a layer of meaning to the text instead of illustrating it in the most basic sense.” Like D’Agata’s text, the paintings are instantiations of tries. The layer or layers of meaning generated by these paintings are not direct, yet they do not obfuscate. Instead they provoke questions about painterly abstraction and technique. How were these strokes made? What meaning exists in their persistent abstraction? Perhaps more importantly, Bernadet’s paintings are gestures towards a larger goal: the attempt to understand the uncertain and abstract nature of existence. In On Knowing & Not, D’Agata and Bernadet present thoughtful, sustained, and skilled interpretations of indeterminacy as a quality of existence. This attempt is not a pursuit of the definite. This is a pursuit with no defined end.

Will the emotional power of Munch’s Scream span 10,000 years? Will the allegories in Gauguin’s Noa-Noa be discernible in the next millennia? Will humans continue to search for meaning or will the gods dissolve the world back into mud? Will they punish us for our obsession with factuality, our mistrust of the complex? How long will people associate attempt with failure? When will we recognize the value of knowing and not knowing?