ANCIENT ARTS OF THE ANDES

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART (WENDELL C. BENNET) (1954)

This book deals with the arts of the pre-Columbian civilizations of the Andes and with related arts from the adjacent Amazon region and southern Central America.

It is often impossible to trace the direction of the flow of influences from one cultural center to the other throughout the Andean area. In some cases the kinship between two style from distant regions seems obvious yet lack of knowledge makes it impossible to state whether these similarities are the result of migrations, of military or spiritual conquest, of trade, or of a common cultural background.

An unusually well documented example of the rapid distribution of an art style over a large area is seen in the spread of the Inca style during the expansion of the Inca Empire. At its greatest extent the Empire reached from what is now northern Chile to central Ecuador, a distance of well over two thousand miles. It included large population centers whose varied cultures had produced highly individual art form of their own long before the relatively short period of Inca rule / cultural trade not always a result of conquest and colonization

the andes

Many advanced civilizations had been built up in different parts of highland Andes and the adjacent Pacific coastal plains (pre-discovery by the Europeans in 1492), but although these shared a common cultural basis and exchanged ideas, they were never finally united into a single political system until incorporated as parts of the Spanish Colonial Empire. However, the Inca had gone far in building an extensive empire before the arrival of the Spaniards, and in earlier times, kingdoms of some magnitude existed.

CENTRAL : mountains and Pacific coast of modern Peru, with some extension into highland Bolivia

SOUTH: northwest Argentina and Chile

NORTH: mountain regions of modern Ecuador and Columbia, with some extension into Panama, Central America and parts of Venezuela

EAST: the Amazonian tropical forest

Long-term time sequences have been tentatively established only in the Central Andes / many of the cultures must be left "floating" in time until further work has been accomplished.

the central andes

The civilizations within the Central Andes shared more with each other than they did with their neighbors to the north, east and south.

Subsistence: intensive agriculture, herding in the mountains, fishing along the coast - goods distributed by trade

Crafts: ceramics, metallurgy, basketry, weaving

Building: permanent materials - stone, adobe

Lifestyle: population concentrated in villages with political organization in village units; leisure time

cultural groups formed by basins, rivers and valleys

1200 BC to 1532 AD (six major time periods) - no form of writing or recorded calendars, dating is based on radio-active carbon dating

STRATIGRAPHY (cultural and archeological) : building over building, grave over grave

The earliest inhabitants of the Central Andes, like those elsewhere in South America were the nomadic hunters, fishers and gatherers who had pushed southward from North America through the Isthmus of Panama

PERIOD ONE (1200 to 400 BC)

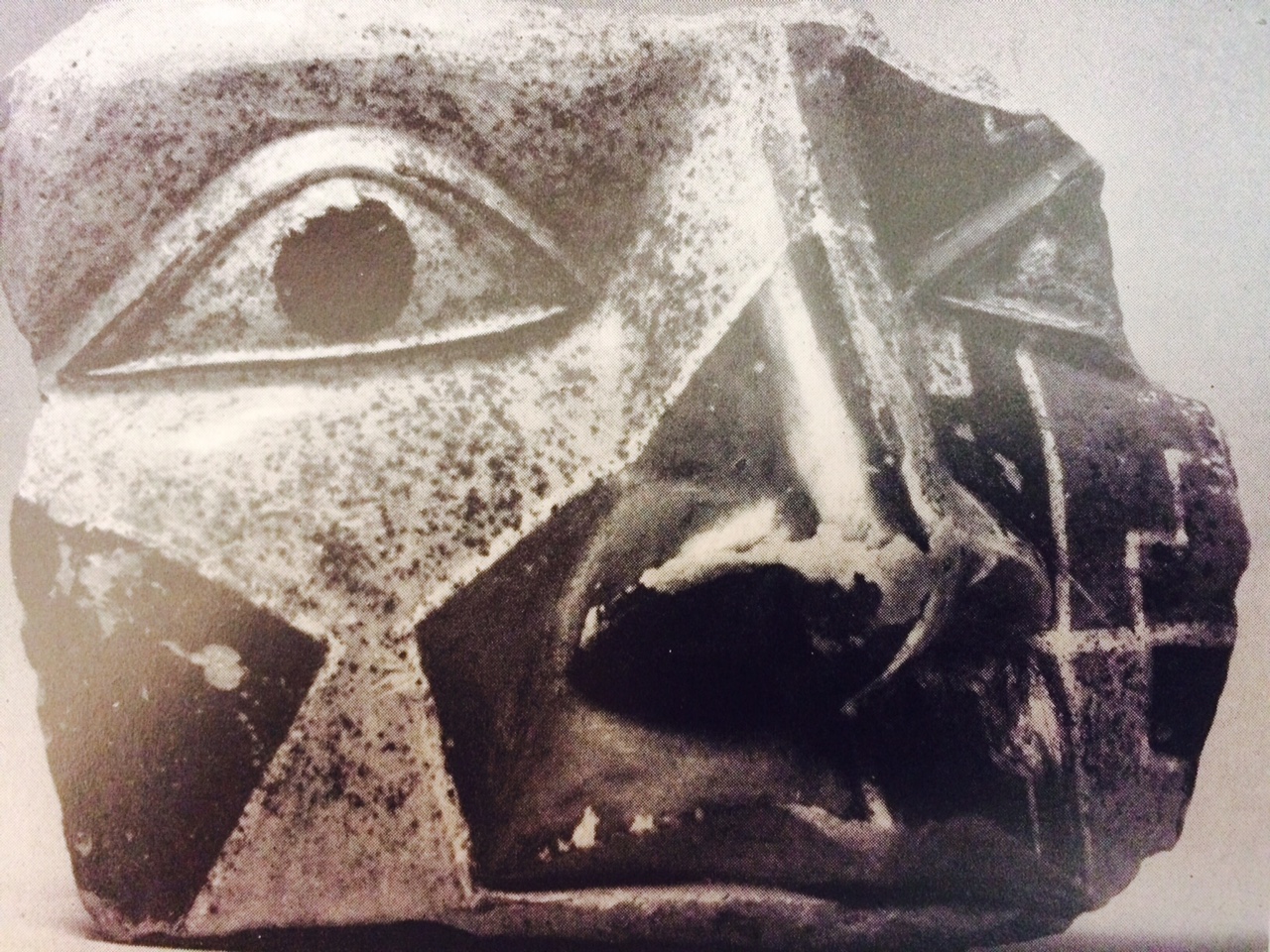

CHAVIN

Occupied a valley region, the Chavín de Huántar (religious site and capital of the Chavín culture), flanked on both sides by high mountain ridges / stone carving defines the Chavín style / carving in the round is largely limited to animal and human heads with projecting tenons for wall insertion / flat carving is represented by wide and narrow stelae, like the Raimondi stone - the carving is in low relief / tendency to cover all of the available surface

the feline / even if the carvings represent other creatures, certain characteristics of the feline can always be detected in them / no other pre-Columbian culture shows such an overwhelming predilection for a single pervasive design motif

the valley could not have supported a large permanent population / no signs of extensive habitation - perhaps was a gathering places for religious ceremonies at certain points in the year

PERIOD TWO (400 BC to 400 AD)

The second period of cultural development in the Central Andes is characterized everywhere by experiments leading to technological development. On the coast, walls are built of conical, ball-shaped, cylindrical, hemispherical, and rectangular adobes.

SALINAR

PARACAS CAVERNAS

"Figure of a flute-player; a very early representation of a person in an everyday pursuit."

PERIOD THREE (400 to 1000 AD)

The long period of formation and experimentation culminated in the mastery of techniques and the establishment of flourishing culture centers in every major region of the Central Andes. The architects directed the construction of large public works and enormous temples. Each local culture was capable of maintaining its own pattern in spite of the numerous influences from neighbors.

MOCHICA

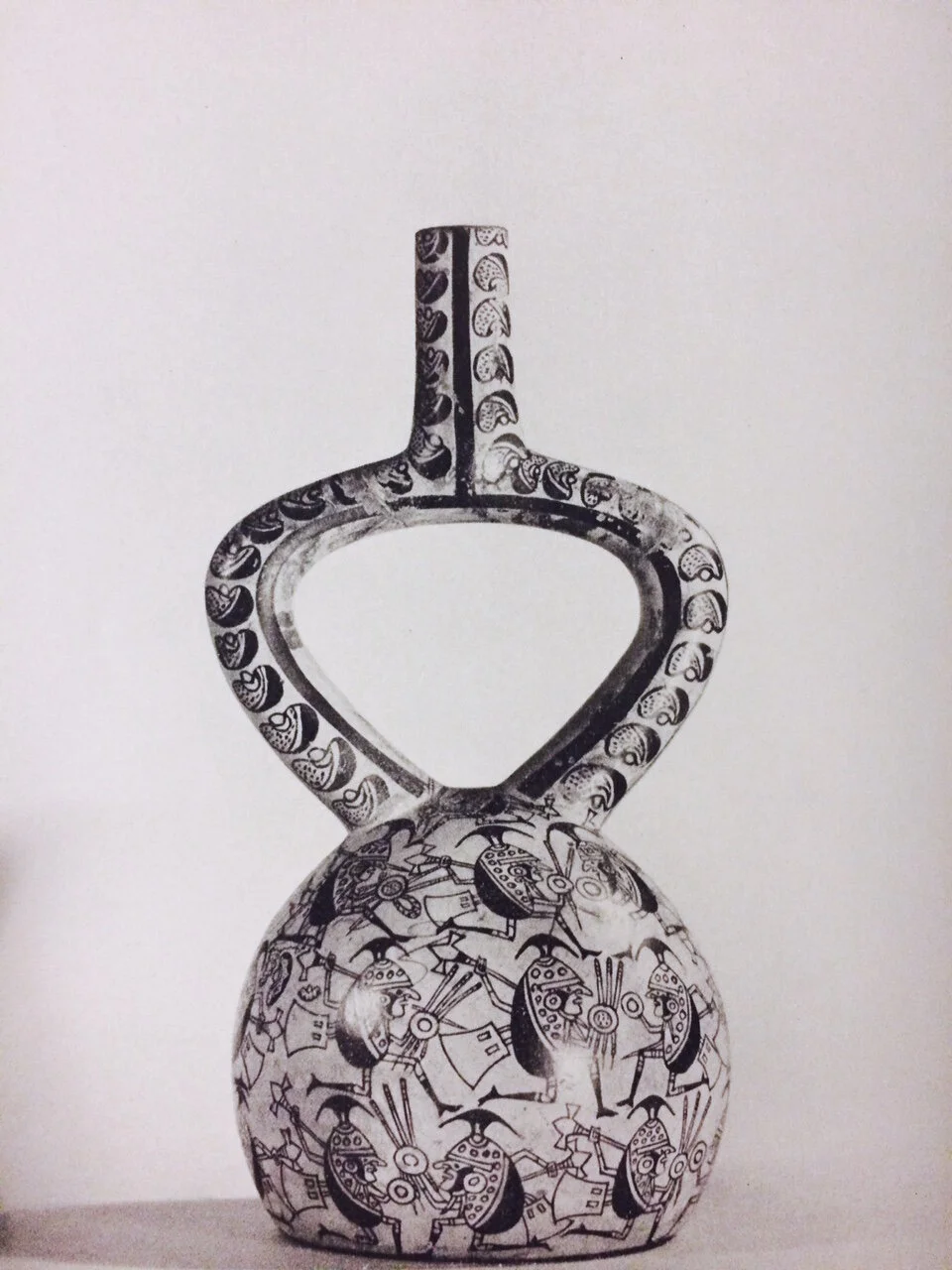

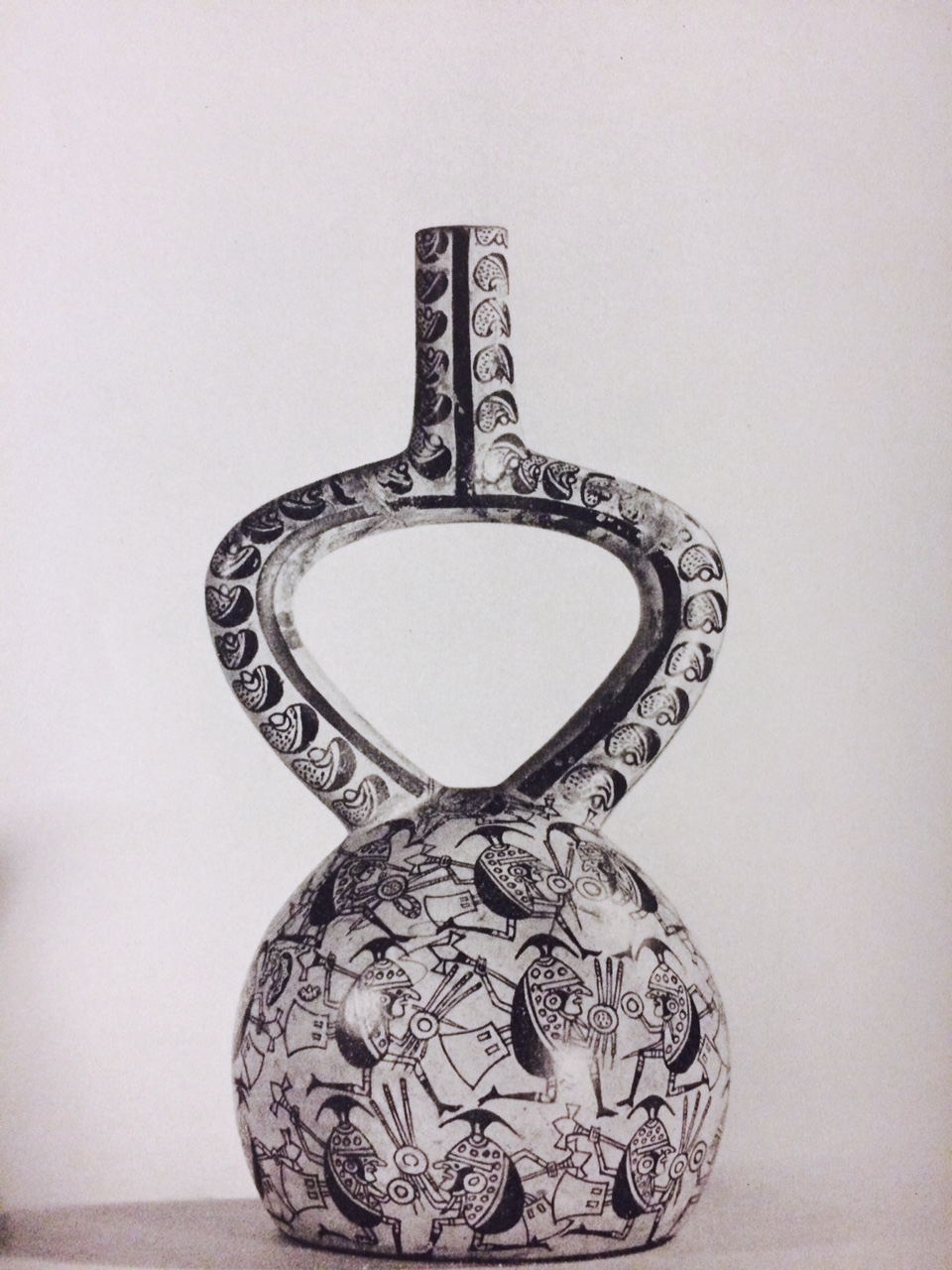

Located in the North Coast valleys of Chicama, Moche and Viru. The Mochica is one of the best-known prehistoric cultures in the Central Andes, in part because of the numerous surface remains and rich burials but likewise because of its faithfully realistic art style. The local flora and fauna are reproduced so accurately that the species can be identified. Sculptured head jars are so individual that they can properly be called portraits.

Stirrup-sprout jar, representing a battle between magic bean warriors. Mochica. Clay, 10 3/16'' high.

The major Mochica architecture was directed towards the erection of great unit pyramids, some built on the open plains, others capping natural ridges. The Huaca del Sol, not far from the town of Trujillo, is probable the largest of these pyramids. A gross estimate of the number of bricks used in this structure runs over 130,000,000.

Huaca del Sol. Northern Coast of Peru. Located at the center of the Moche capital city, the temple appears to have been used for ritual, ceremonial activities and as a royal residence and burial chambers.

It is the ceramic art which is preserved in greatest quantity and which is the most representative of the Mochica. The outstanding characteristics of the Mochica ceramics are the skilled modeling and the delicate painting in red and cream white.

Portrait Jar, Mochica. Clay, 4 1/8" high. A fine example of realistic portraiture typical for the culture and otherwise very rare for pre-Columbian America.

The realistic designs, supplemented by other archeological information, give a broad picture of Mochica culture. The basic emphasis was on farming, as confirmed by the great attention to plants in the ceramic decoration, and by the remains of mammoth aqueducts which served as parts of the irrigation system. Hunting is depicted in the paintings as a sport for the privileged.

There were many specialized groups, such as warriors, messengers, weavers, medicine men, priests, dancers and musicians. The ceramic designs also indicate a hierarchy of gods represented by animals, birds, fish, plants and humans, but further identification involves speculation. In spite of the high artistic achievements, there seems to have been an urge, later crystallized by the Inca, to reduce everything possible to unit labor and mass production.

Double vessel, Mochica. Clay, 6 3/4". If this vessel is dipped when filled with liquid, it emits a mournful sound, which accounts for the open mouth of the figure.

PARACAS NECROPOLIS

The Paracas peninsula, near Pisco, was a burial ground for the Necropolis culture. The Necropolis burials are found in subterranean, rectangular rooms, lined with rough stones and small adobes. In 1925, Julio C. Tello removed from these rooms over four hundred mummy bundles. The desiccated body occupies but a small portion of the bundle, the bulk being built up by numerous cloth wrappings.

The body of the deceased has been viscerated and dried and placed on a large circular shallow basket in flexed position, that is with the knees drawn up under the chin. Offerings had been put next to him, such as dried meat, wool, beans, maize, cotton and peanuts. The body itself was dressed in simple clothing and the head adorned with a turban to which feathers and gold ornaments were attached. Then layers of cloth had been wrapped around. At this point the upper portion of a plain cloth wrapping was bunched and tied to form a false head. The enlarged bundle with its false head was then treated as though it were the body. The false head was decorated with a turban and the bundle adorned with shawls and shirts. The padding and wrapping process was continued and a new false head was formed. In this bundle, there were four such stages of wrapping, which suggests a ceremonial procedure, perhaps at four time periods, in which the bundle was dressed in new wrappings for the ceremony and then reinterred.

Julio C. Tello with a mummy bundle.

Cross-section of a mummy bundle.

The Paracas Necropolis is justly famed for its turbans, ponchos, skirts and shawls characteristically decorated with over-all polychrome embroidery. The designs are elaborate stylized cat demons, birds and anthropomorphized figures, arranged in repeat sequences, often alternating right side up and upside down.

The amount of time required to spin, dye, weave and embroider any one of the thousands of large Paracas textiles must be estimated in years. In spite of the quantity of material, it is difficult to point to one piece which is better or poorer made than another, and the designs, in spite of their complexity, are amazingly consistent. When the quantity of weaving is reviewed in terms of available weavers, we are presented with a picture of a people devoting the major part of their leisure time to the skilled production of textiles predestined to be interred with their ancestors. It is not surprising that such a people would be little concerned with the erection of great temples, or elaborate political systems.

Detail of embroidered mantle, Paracas Necropolis.

NAZCA

On the deserts, flanking the Nazca valley, airplane pictures have revealed an intricate maze of lines that extend for miles and curve to form figures of various kinds. There has been much speculation about the purpose of these lines, or paths, all clearly of artificial construction. It is particularly provoking since the designs could only have been seen from the air. Some have suggested that they resulted from calendrical observations, or that they were symbolic representations of genealogical trees. They might also have been markers for ceremonial parades by a people who devoted much of their life to weaving for their ancestors and who thought nothing of marching for miles onto a desert peninsula to inter their dead.

Aerial view of Nazca Lines intersecting the Pájaro (“Bird”), possibly a representation of a condor, approximately 443 feet (135 metres) in length, near Nazca, Peru.

This aerial photograph was taken by Maria Reiche, one of the first archaeologists to study the lines, in 1953.

PERIOD FOUR (1000 AD to 1300 AD)

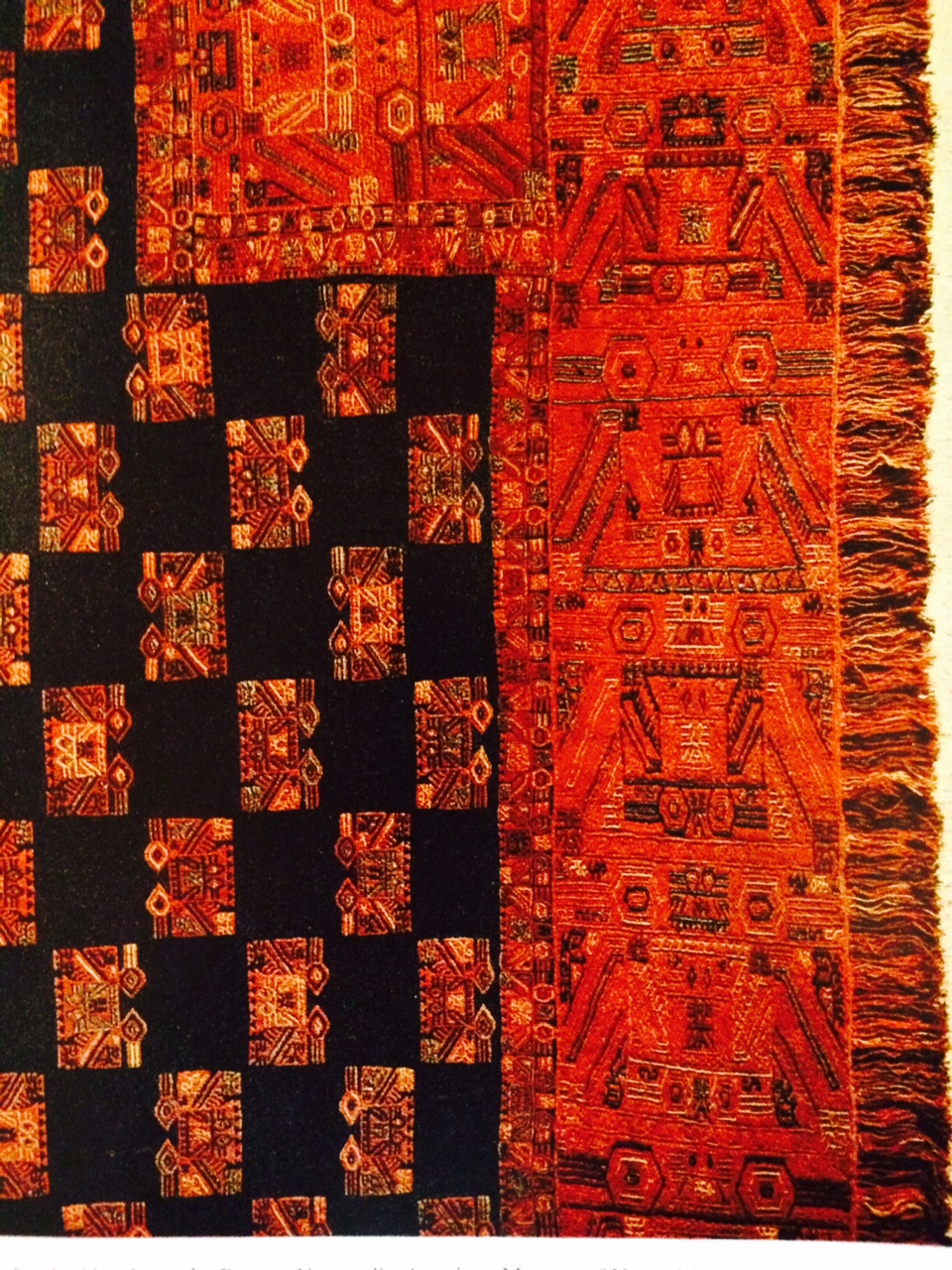

The fourth period is dominated y the Tiahuanaco culture which extended its influence and perhaps its control over most of the Central Andes. The Tiahuanaco expansion is traced by a distinctive design style, a ceramic type, a color scheme and a weaving pattern. It is still uncertain whether the wide spread of these features was by peaceful or military means, but in any event, local cultures everywhere were wither merged with Tiahuanaco or eclipsed.

BOLIVIAN TIAHUANACO

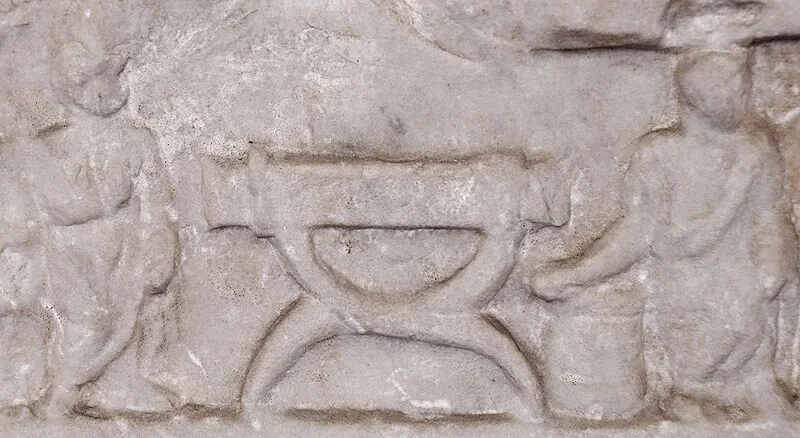

The famous ruins named Tiahunaco lie on the Bolivian side of the Titicaca basin some twelve miles south of the lake. The site is composed of a series of construction units spread out over an immense area. Although each unit is symmetrical within itself, no geometric system can be discovered in the overall plan.

The famous monolithic stone gateway, called "Gate of the Sun" is associated with the Calasasaya construction unit.

Monolithic doorway "Gate of the Sun" at Tiahuanaco, Bolivia

Tiahuanaco, like Chavin de Huantar, was probably not a great population center, but was rather a religious site to which pilgrims came for annual ceremonies and were put to service hauling stones, dressing them, and constructing temple walls.

Many examples of stone carving have been found at Tiahuanaco. There somewhat realistic statues representing kneeling or seated figures, with projecting cheek bones, jutting jaws, and flaring lips; boulder-like heads; pillars carved with simple features; and slabs with angular, geometric designs.

Sculptures. Tiahuanaco, Bolivia. Stone. These sculptures show a realism unusual in the Tiahuanaco style.

PERUVIAN TIAHUANACO

Fragement of a face. Coast Tiahuanaco. Clay, 3 3/8" high. Part of a large jar showing a realistic face covered with polychrome geometric designs.

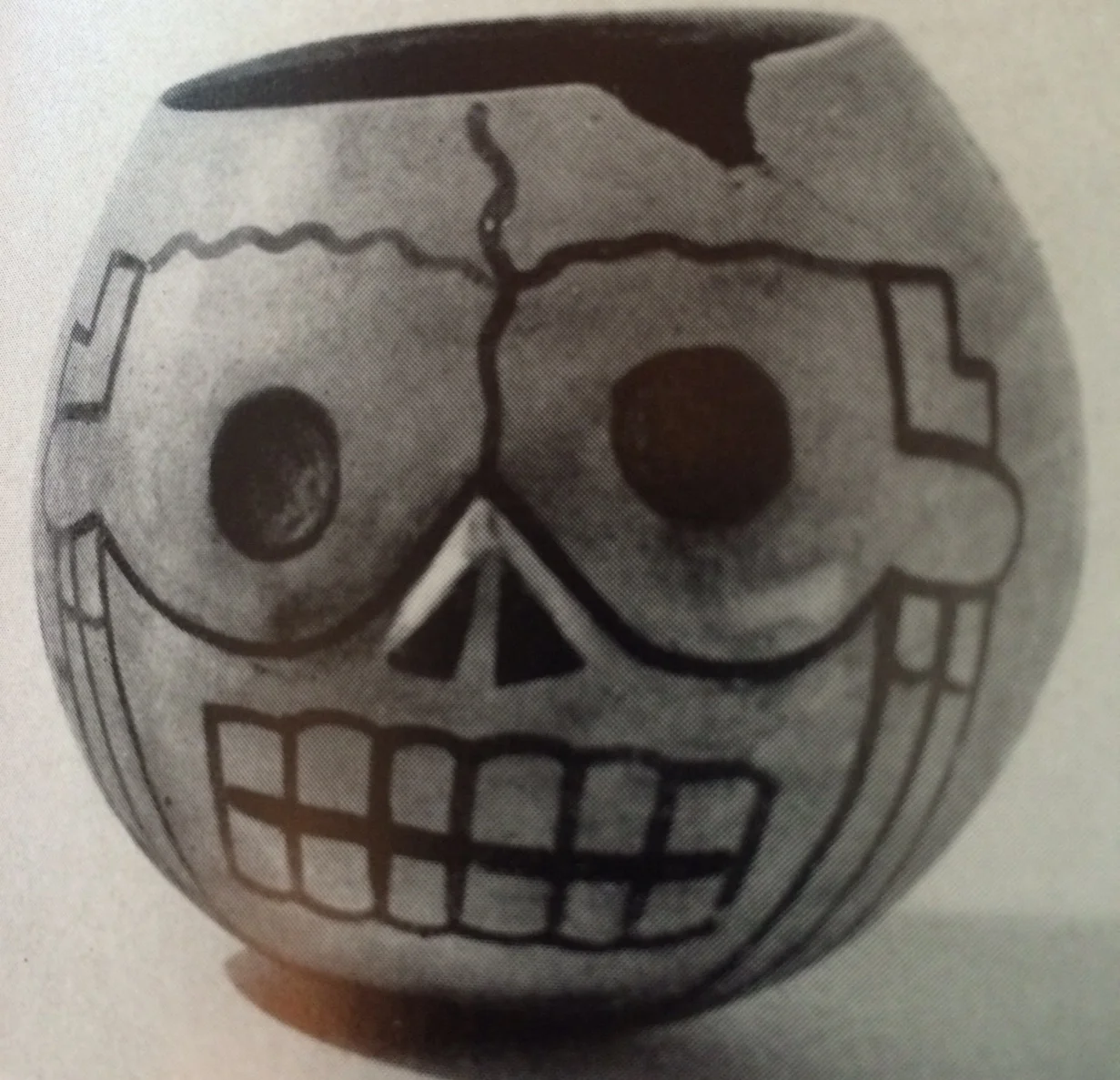

Bowl in the shape of a skull. Coast Tiahuanaco. Clay, 4 1/4" high.

Detail of fragment of poncho in tapestry weave with highly stylized feline design. Coast Tiahuanaco. 19 5/8" wide. Collection: Nelson A. Rockefeller. Photo Nickolas Muray.

PERIOD FIVE (1300 to 1428 AD)

The new emphasis was on political organization. Populations were reshifted into large habitation centers, some of which reached city proportions. Because of the increased awareness of the threat of invasion, forts were built at strategic points and garrisons established at them. The shift in emphasis is reflected in the craft products which, although still in produced competently and in quantity, lack quality and artistic inspiration.

CHIMU

The Chimu control was extensive. The population was large and well organized. Extensive irrigation systems allowed the cultivation of every available acre of land. They had two types of cities: garrison towns and ceremonial cities. Chanchan is one of the largest ceremonial cities, covering over eight square miles and containing ten major units. The building is almost entirely of large rectangular adobes, and the walls are coated with clay plaster and often decorated with relief arabesques of rows of birds, humans and animals.

The early Spanish documents contain a few rare accounts of the "Kingdom of the Chimor," as the Chimu organization was called. It is described as a sharply class-divided society with a definite ruling group and great masses of commoners. Once again most of the features which characterize the Inca Empire are already present in the Chimu pattern.

PERIOD FIVE (1438 to 1532 AD)

THE INCA EMPIRE

The review of the early history has shown that most of the features of Inca culture were based on past cultural developments.

In 1532 when Francisco Pizarro sailed from Panama down the Pacific coast to Peru, he encountered eventually destroyed the Inca Empire, the only truly organized political state of the New World in pre-Columbian times. The Empire was large in size. At the maximum, it included the mountain and coastal areas from the southern border of Colombia to central Chile, a total of some 350,000 square miles, the equivalent of the Atlantic seaboard of the United States. Population could have been as large as 7 million people.

The vast territory with its divergent populations was welded into a true political sate founded on organized military conquest. The Inca were not content merely to extract tribute from the conquered people but instead tried to incorporate them into a political whole. Once people were subdued, the process of incorporation was systematically applied. A topographic model of the region was made and a census taken. Forts were built and army garrisons established. Roads were constructed to link the new territory into the system. Important hostages and the most sacred of the local religious objects were taken to the Inca capital of Cuzco. If the population continued to be rebellious, whole villages might be moved out to another section and pacified groups moved in to replace them.

The Inca Empire was based on intensive agriculture. Over forty domesticated plants were cultivated, many of them well-known American species such as corn, bean, squash, potato, cotton and tobacco.

Organizational structure: the DECIMAL PYRAMIDAL PATTERN: at the base of the pyramid was the puric the able-bodied male worker. Ten workers were controlled by one straw boss; ten straw bosses had a foreman; ten foreman in turn had a supervisor, ideally the head of a village. The hierarchy continued in this fashion to the chief of a tribe, reportedly composed of ten thousand workers, to the governor of a province, to the rule of one of the four quarters of the Inca empire and finally to the emperor, the Sapa Inca, at the apex of the pyramid. Very little communication between officers of the same rank - this has been claimed as one of the major weaknesses because when Pizarro seized the emperor himself there was no on authorized to give the orders.

The dualism between the aristocracy and commoners was emphasized in many if not all aspects of life, including religious practices. The Inca state religion, superimposed on all sections of the Empire, was complex and marked by elaborate ceremonies. In contrast, the religious practices of the local villages of the commoners consisted of simple rituals for curing the fields and the sick.

The early documents offer rich details on many aspects of the Inca culture, and the numerous archeological remains serve to confirm the historical records. Although the conquering Spaniards shipped many examples of Inca craftsmanship back to Spain, few if any of these collections have been preserved. Consequently, the principal collections of Inca artifacts are the results of relatively recent archeological investigations.

The Inca are famed for the quantity and variety of their stone constructions. They are particularly noteworthy as road builders since their elaborate system of highways formed a network throughout the entire Empire (almost 25,000 miles of roadway).

The Inca expansion was the most extensive ever witnessed in the Andean region.

Wall with three windows, Machu Picchu. Inca. Photo Heinrich Ubbelohde Doering

Much I have excerpted from various sources.

Please note that I do not own the copyright to most of the texts, images, or videos.